OPENING

FRIDAY 20.02.15 AT 7PM

EXHIBITION

21.02.15 – 05.04.15

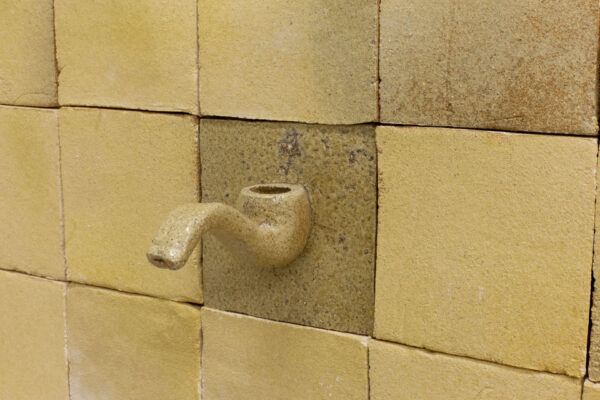

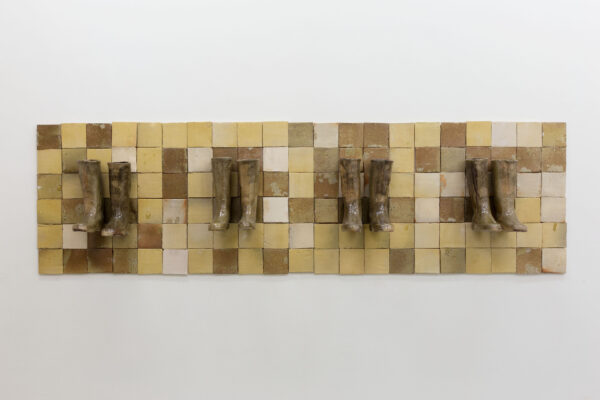

Ceramic tiles and toilet pots, dogs and carp, gardening boots, pipes and flutes: the work Daniel Dewar & Gregory Gicquel have made for Etablissement d’en face blend motifs of the pastoral outdoor with the sanitary interior. But my first thought on its composition mode of rhythmically repeated bas-reliefs and objects was its reminiscence to the interior of a Pharaoh’s tomb: a composed-computational sum of image-signs and objects that are as much practical as allegorical vessels. One particular object stored in these Egyptian tombs, among magic bricks, canopy jars and miniature copies of servants, was a small blue faience sculpture that could be described as the forelegs of a bovine animal -like those of a cow. These faience forelegs represent the Egyptian word-sign whm meaning to ‘repeat’. It may insinuate some form of perpetuity, which would make the object a sort of sculptural multiplication sign to accumulate and expand the already plenty.

Dewar & Gicquel’s work is much less metaphysical, yet, the physical quantity and elaboration of the Pharaoh’s rebus-like interior -functioning as a vessel directed towards a fabled beyond-region- offers an alternative vantage point on the Pastoral in relation to the interior.

From the start the pastoral was an escapist fantasy of the alienated city-dweller. Originated as a poetry genre at the heart of the Hellenist city, it described an idyllic rural life of carefree shepherds courting ladies over green pastures, easy-listening to the song of a flute. Later on, in the Renaissance, the pastoral was introduced as a painterly motif as well as a theatrical genre. By now the pastoral held a surplus-reference to antiquity itself, now located in Arcadia: a sublimated rural region, celebrated as a harmonious wilderness, often representing a utopian ideal. Yet again, it was the escapist vision of unattained beauty and liberty of a citizen who felt confined to the cultured interior of city-life. As an artistic and idealistic motif, Arcadia returned during the period of classicism. Only in the early industrial society of the 19th century did it find a novel successor -or at least a relay- in the form of colonialism’s aesthetic supplement; exoticism. Exoticism was of course already introduced earlier within the arts, but by mid 19th century, it was all the rage and a tremendous influence on the applied arts and interior decoration. Exoticism told a sensuous tale of opulence and barbaric splendour, yet was equally associated with the virgin integrity of the noble savage. Designs of pre-industrialized cultures were appreciated for their purity and uncorrupted elegance and considered superior in quality, contrary to Capitalism’s factory mass-produced utilitarian design. By the turn of the century the exotic had of course become a mass-product itself. Peter Sloterdijk considers the second half of the 19th century and the Crystal Palace World fair in London as the metaphorical beginning of Capitalism’s global interior: a mundane climate-controlled hothouse in which distances between continents became nil, in which diverting flora, fauna and technical innovations from all over world are gathered under one roof. The transparency of the glass wall confirming the difference between those who are inside and those who are out. Exoticism, as the great Outer-Other fantasized from within the controlled and cultured interior, has often been seen as an important step towards art for art’s sake. Certainly the influence of the exotic, on the applied arts and interior decoration, was a distinct step towards the total-environment in the arts: the interior as inside -outside of the world (it is of no surprise that the earliest science-fiction stems from the same period).

Another level and type of interior, which the 19th century brought along, was the bathroom and its Water Closet. Restraining and containing the hazards of wastes, the sanitary confinement shone its light, and prudishness followed in its shadow.

In Dewar & Gicquel’s installation it is the repeated motif of the toilet-pot that stands out the more classical Pastoral motifs. In its clay/stoneware version it is hard not to see the toilet-pot as an ode to the vase and an allegory of sculpture it-self. It is both shape and container, form and content. In the days before flushing, when the Water Closet was still just an earth-closet, the aforementioned content was euphemistically, and quite poetically, referred to as ‘night-soil’. It was primarily in urban areas that night soil collectors would come regularly (at night) to collect human faeces with the purpose of serving as agricultural fertilizer, disposing the excrements in isolated rural areas and farms; those all-inspiring plains of the pastoral. With the multiple -shared- toilet-pots, Dewar & Gicquel provoke the comfortable confinement of prudishness with cultured longing for impudence, now freed of shame.

This is where a distinct difference comes in between Dewar & Gicquel’s scenery and the aforementioned historical escapisms. For Dewar & Gicquel the pastoral is not just a motif or a theme, it is also an attempted ideal of living through the actual production-mode. On the subject of production the two artists have, by now, already a reputation that precedes them. Indeed they love to make everything themselves -with their own hands- and master every technique (all present ceramics were fired in their self-build kiln and they emphasize that it is stoneware -not earthenware) and they love to make it big and plenty. So, the idyllic for them is not one of leisurely play, but one of surplus-energy, dirt, dust and sweating bodies, if possible outdoors, and in the countryside. It’s working as a sport and the endorphins that come with it. With the pleasure of making, and of making it big, we can also assume that the sweating of the hard working body offers the liberating excuse to be naked as much as possible.

Classically the pastoral contains no program, contrary to the utopian project. Though Arcadia already was a heroic upgrade, in Dewar & Gicquel’s interpretation of the pastoral, this has been supplemented with an emancipatory dimension. It comprises -in the Nietzschean sense- an enhancement of life rather than a revolution. At best, this ‘enhancement of life’ is what is conveyed through their work. It is of course hard to say whether preceding reputations will not one day become haunting ones, but all the same it is a clear and present stand in their work, one that inspires questions on the active life.

In her book The Human Condition (1958), Hannah Arendt reflects on the Vita Activa as a philosophical alternative to the Vita Contemplativa, defining and analysing labour, work and action as three distinct categories of being-in-the-world. She defines labour as the life-sustaining production of necessities in remorseless repetition, a state of survival; something one is subjected to. Work is defined as an interaction between the natural world and human artisanship, involving the conversion of an idea into a thing, creating a difference between labouring and fabrication. Finally action is seen as the interaction between people without (or beyond) the intermediary of things or matter. It is a disclosure, revealing “who” is acting, as distinct from “what” they are. To act is not something that can be done in isolation, she argues; it is done in a plurality the same way a performer needs an audience.

It may be a free-style interpretation, but it’s tempting to consider the work and the method of Dewar & Gicquel as interconnecting the aforementioned categories of the active life. For sure, the Vita Activa can be seen as a potentially philosophical dimension in their work. If they subject themselves to remorseless repetition, they do this of course by their own choice; taking labour as a free format and the giant-size production to which they subjugate as a liberating one. If anything, their actions go through the intermediary of matter and object, but the presented work transpires the performance of its process: the disproportionate and excessive energy-expenditure. The pleasure of making – of having something appear and its appearance coincide. What they show is always where it came from, and who made it; fabrication and how this transpires through appearance are central in their work. Dewar & Gicquel are not dilettantes; they are skilled artisans. But do you fight against or surf on the rekindled wave of artisanship in the art-world knowing how much of its appreciation is fetishized? Mastering a craft or a technique’s tradition places Dewar & Gicquel in a generational and cultural plurality. This is something they do consciously. The experimental is lived as experience; a gap in mastery holds a promise to learning. It may sound pompous but there seems to be an engagement in this. It’s about how a craft organizes the daily life.

Michael Van den Abeele