OPENING

FRIDAY 14.11.08 AT 7PM

EXHIBITION

15.11.08 – 20.12.08

At the request of Etablissement d’en face Jacques Charlier (b.1939 in Liège) has reinstalled ‘Zone Absolue’, an exhibition and event dating from 1970 that was shown in Liège in the former APIAW (Association for the intellectual progress and artistry of Wallonia). In this exhibition Jacques Charlier shows the artist’s autonomy from and engagement with society, that most certainly still comes across as modern in the present day.

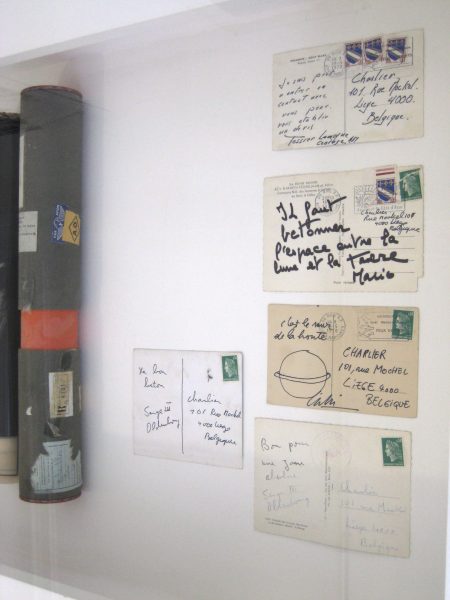

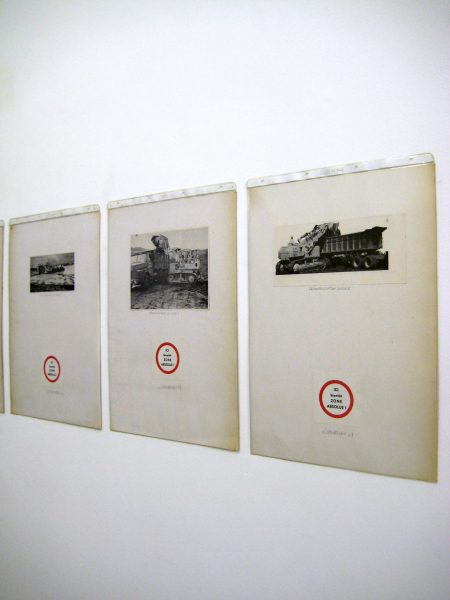

In the late 1960s and beginning of the 1970s, in order to earn a living, Charlier worked as a draughtsman for the Province of Liège – Technical Service (STP), an administrative service that planned and maintained infrastructure works (roads, sewerage, etc). As an artist in what has since become known as the STP-period, Charlier realised much work whereby he plucked images and work material, methods and documents directly out of his fellow civil servants’ professional milieu, to include them as reality in his art.

Along with other things in the late 1960s (May of ’68) there was a lot of commotion in Liège regarding the planned modernisation works in the city, in which roads were destined to run directly through the centre. Charlier was not insensitive to this. As an artist he stood in direct relation with situationism. Thus from 1965-68 he published different editions of Total’s ‘l’édition souterraine liègioise’ (the Liège underground edition), a stencilled paper with input from diverse people in his locale. That paper testified to a sharp, lucid manner of ‘being in the world’, without entertaining any form of illusion. Or, such as presented in the first number: ‘TOTAL is the spectacle of life in general and of our own life. It does not hope, nor fight for a new utopian ‘freedom’ in which any man would finally become aware of himself. It is content to survive in the secret corridors, without wishing to persuade. That one regards us as alive is enough.’

Following the protests of ’68 the management of the APIAW – in a burst of democratic concern – decided to ask the artists themselves who could provide a subsequent exhibition. After two rounds of voting the choice finally fell on Charlier. He made this exhibition there, that thanks to his proposal for the realisation of an ‘absolute zone’ grafted itself onto the heavy weight that hung over the city of Liège; the imminent infrastructure modernisation works and the protests of the city- and nature-minded sections of the population. As the text on the plans of the Absolute Zone proves, this is, in the first instance, a conceptual design that can be adjusted to fit a smaller area, can be extended to apply to the whole city (i.e. Liège) and can even be executed at the scale of the entire planet. With this Charlier presents, in a sarcastic way, a complete solution to the problem concerning housing, mobility and people in general. And he does that through two fundamentalisms of his time – the modern and ecological movements – radically and paradoxically placing them next to one another.

In the remaining work on show Charlier likewise attests to a disenchanting commitment. The Transparant Flag (1966) was borne by leaders of the group Total during the first anti- atom bomb protests in Brussels in 1968 with this pronouncement, as Charlier told Jean-Michel Botquin in a conversation: ‘In regard to the demonstration, besides affirming this idea of transparency of which I come to speak – the more transparency became the object of concern, the more the mystery thickened – it was also, to some extent, to bring back a kind of coldness within the procession, to reduce the temperature, like a counter-proposal with megaphones and drums. We have to create a zone of silence. It was a way of saying that nothing occurred, that reality was other, that this theatricalization made little sense. It was, in a certain way, to protest about the manner in which the protest was being theatricalized, while supporting the object of the protest.’

In the performance ‘Canalisations souterraines’ (underground drains) (1969), filmed by Nicole Forsback, Charlier carried out true Sisyphean labour in the absence of any public, apart from a few frolicking youngsters. In this performance, on a heap of detritus from the coalmines, Charlier dabbles with that inert material and a white sailcloth. An allegory of hard daily labour, standing in sharp contrast to the then known forms of land art.