WITH PATRICK ALLEN, CHRISTIANE BLATTMANN, BRADLEY DAVIES,

MARLIES DE CLERCK, MIKE D’IPPOLITO, LAURENT DUPONT,

MATHILDE FENGER, MONA FILLEUL, HADRIEN GÉRENTON, JOS DE GRUYTER &

HARALD THYS, ALEXANDER PAGE, AND CHARLOTTE VANDER BORGHT

OPENING

SATURDAY, 01.06.24

EXHIBITION

02.06.24 – 01.09.24

AT SIMIAN

KAY FISKERS PLADS 17

2300 COPENHAGEN

DENMARK

THIS PROJECT WAS SUPPORTED BY:

THE EUROPEAN UNION & GOETHE INSTITUT,

AND FLANDERS STATE OF THE ART

“The public is an examiner, but an absent-minded one.”

-Walter Benjamin, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction

In New York City, there is a woman named Niki Logis. She taught sculpture at The Cooper Union for approximately 1000 years. She once invented and then fraudulently attributed a quotation to Martin Heidegger: “a painting hangs off the wall, like a hat, or a gun.” In a vulgar way Painting-as-Prop hangs from this observation, just the same as a painting hangs from a wall. In a similarly vulgar way, the curatorial intention behind this exhibition is one of generating dissensus. Jacques Rancière injected this term into the sphere of contemporary art by relating it to a phenomenological rupture between seeing and thinking: “dissensus is the conflict between a sensory presentation and a way of making sense of it,” or “conflict between several sensory regimes or bodies.”1 He stresses that the nature of such a conflict makes anticipating its arrival impossible. So at the outset, our curatorial intention is destined to failure. While Rancière’s intentions– to emancipate spectators from any number of shadowy caves – are very different from our own, nevertheless his aesthetic model of irreconcilable differences remains our starting point. Contemporary aesthetic theory is not unlike a dysfunctional and codependent marriage– when irreconcilable differences arise, things become once again interesting.

i.

Drawings and paintings were once uniquely synonymous with images– there was not yet an alternative form they could take. Yet it was still possible for Victor Hugo to anticipate the metaphysical changes that the image would soon undergo when he declared that the printing press had effectively killed architecture. Regardless of whether the printing press, photography, or technological reproduction did or did not murder their predecessors, for some time now it has been apparent that images are not objects.2 While the witticisms of Ad Reinhardt are unusually compelling, his paintings remain more likely to be leaned-against in moments of thoughtless exhaustion than are sculptures to be accidentally backed-into in moments of breathless reverie.

Paintings are of course objects– they hang on walls; they are professionally handled, wrapped in plastic, put in boxes, and transported by truck; they are bought and sold, remotely or in-person; they can be damaged, insulted, or destroyed. In order to consider such a proposition, we must first try to differentiate, however vaguely, between images and objects. In any case, our investigation is not of objects or their dubiously imagistic nature, but of a very specific type of object: the prop.

Any discussion of ‘the prop’ must, as a matter of course, dip its wretched toe into the muddy trough of semiology. In 1940, a Czech theatrical theorist named Jiři Veltruský cast a wide net in saying that “all that is on the stage is a sign.”3 Veltruský was part of a circle of linguists and thinkers in Prague that theorized the semiotization of objects, “a process which is clearest, perhaps, in the case of the elements of the set. A table employed in dramatic representation will not usually differ in any material or structural fashion from the item of furniture that the members of the audience eat at, and yet it is in some sense transformed: it acquires, as it were, a set of quotation marks.”4

The prop can be further distinguished through more relational perspectives, like that of the psychoanalyst D.W. Winnicott, who thought that “there is no such thing as a prop, wherever a prop exists an actor-object interaction exists. Irrespective of its signifying function, a prop is something an object becomes, rather than something an object is.”5 Said in another way: props are objects which come into being through their interactions with things outside themselves. A prop is an object which represents itself, and it does so once it is semiotized appropriately. The specific mechanics of semiotization of objects into objects which perform themselves will be looked at more closely later in this text, but one such appropriate context which contributes to the semiotization of an object is most usually that of the theatrical stage. In exhibition-making there is a similarly theatrical process of semiotization. Both the theatrical stage and the exhibition space are architectures which radically transform all objects and bodies contained within them.

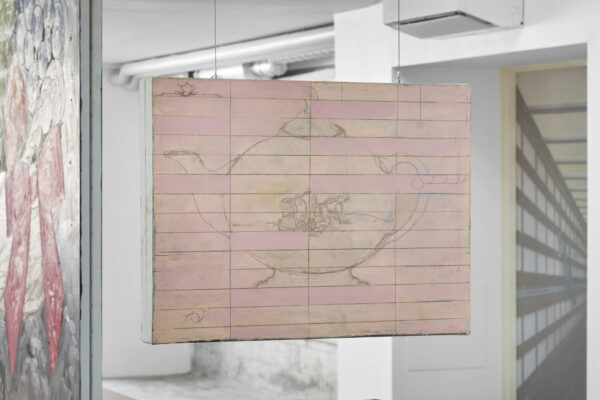

If we are to consider painting-as-prop, would this mean that the exhibition is a stage? This operation should not confuse the art exhibition for a stage, nor naively assert the inverse, but rather to suggest that the two have more in common than they don’t. In fact the contextual distinctions between these two spaces themselves is not important; for our purposes what is important is how bodies and objects interact within these spaces. It could be said that all artworks, by their nature, carry within them an ability to be at once what they are as well as what they represent. However we are interested in a more specific process of signification where the object represents itself at the same time that it is itself– a form of auto-mimesis. This relation is not unlike the surveying of a Borges’ map at the scale of the territory. Within the scope of the exhibition, we see this executed most literally in the work of Laurent Dupont. Dupont’s sculptures are found cardboard boxes which have had their surfaces meticulously repainted. In a manner of speaking, the boxes are paintings of themselves. To varying degrees of literal application, we see this function at play in a number of works in the exhibition. In this way the “prop” and its inherent map-territory relation should be understood as a conceptual framework through which contemporary art can be viewed in opposition to a process of simple production. In performing itself, the “prop” becomes derealized to the viewer– it is transformed into something not quite itself. Here one might suggest a hint of that thinking that characterizes the Capgras delusion in which patients stubbornly believe that their friends, families, and/or acquaintances have all been replaced by identical imposters.

The auto-mimetic nature of the prop is principally dissociative– being both itself, and as a result of its performance, not itself. The dissociation could be thought of as two-fold, whereby the split occuring in object’s semiotization into “prop” equally splits any viewing subject. That is to say that a dissociated object implies a dissociated viewer. The viewer dissociates, seeing herself seeing the prop. The exhibition attendee, dissociated, seeing herself seeing the art. The literal auto-mimetic quality achieved in Dupont’s cardboard boxes is neither requisite nor exhaustive in the construction of the dissociative relation. The relation could be thought of as structurally theatrical in that it implicates its viewer and it is this implicatory mediation that has been the imperative of the theatrical. It is also precisely this theatrical mediating function which has long been misunderstood, disregarded, and even prohibited in visual art. The effect of theatricality as a framework is its radical transformation of the viewer from a spectator who consumes images, into a dissociated subject who performs their role in the consumption of images. The question is: might the dynamic between artwork and viewer be more similar to the stage actor and her prop than it is to the spectator and the spectacle?

ii.

Theatricality is the realm of performance. One might forget such a fact when the term is battered and abused as often as it has been in the modern era. To say that theatricality is the realm of performance is to say that the theatrical is primarily concerned with representation through ostension. “Representation,” one of the artists in this exhibition6 once told me, “is a key to an empty room.” In this regard, representation as such, will not here be unpacked. To summarize a theatrical theory of Umberto Eco, theatricality is ostensive by nature.7 Contemporary art, on the other hand, has more often relied on exemplification as its primary discursive model. In simpler terms, the theater shows where the gallery tells. The distinctions underlying ostension vs. exemplification; mimesis vs. diegesis; or showing vs. telling can be formulated in any number of ways, but it remains a critique of modes of presentation, rather than one of significance. The ideological debate is essentially one of aesthetic efficacy as it relates to didacticism. One does not need to look very far back to find the consequential origins of how the use of ostensive signification as a structural model came to be purged from contemporary art and exhibition-making. Decades before the “artists” and curators associated with the relational art of the 1990s began their open artillery assault upon what they mistook for a barrier separating “art” from “life,” there was a robust history of distaste for ostension in modern visual art.

It was likely the Philistine Michael Fried and his bizarre fetish for “present-ness” – expressed most lucidly in his influential essay Art and Objecthood – which could be considered the inception of the post-modernist shadow ban on “theatricality.”8 Fried’s psychotic proclamation in 1967 that “theater is now the negation of art”9 set the stage for more than 50 years of a visual art which could only ever be permitted to tell things to its viewers. Again, this tell function is a problematic of stylistic transmission; it is a question of form in the most structural of ways. Both showing and telling rely on the assumption of art’s didactic function– it is a matter of attitude in how ideas are transmitted, not what ideas are transmitted.

Fried seemed mostly troubled with the necessity that he exert his forlorn body in order to wholly perceive the modern art of that era– comically enough, medium-sized boxes placed directly on the floor. His unhinged paranoia of being physically “extorted into situations”10 with artworks, brought him to reject art which could not be understood immediately. The true subject of Fried’s critique was the operation of mediation. In 1967 Fried wanted immediate access to the things in front of him – a condition that today is inescapable. Art and Objecthood’s presentness is a rallying call for artworks that are readily capable of being consumed as images. Any forms of mediation– that is, anything outside of an artwork’s immediate presence– were branded as theatrical and thus “hostile to the arts.”11 Mr. Fried, like so many dupes before and after him, failed to engage these unadorned objects in Root Cause Analysis– he mistook a part for the whole. Had he, in 1967, bothered to put down the marihuana cigarette12 and gaze up from his typewriter, he might have seen the writing on the wall– the same writing that so many others saw across the western world during this period: things were changing. The great irony of the argument is that Fried’s aversion to theatricality is fundamentally the same logic as he ascribes to the minimalists which he spurns: “it is largely ideological. It seeks to declare and occupy a position– one that can be formulated in words.”13 The position he declared and occupied and formulated in words, was an impactful miscalculation of the effect of theatricality.

The essential dichotomy of Fried’s analysis of “theatricality” and “presentness” was not incorrect. Rather the problem was his failure to incorporate his analysis into the broader socio-political conflicts and revolutions of the period. Not that it was a failure to properly historicize, but rather that his argument was fundamentally reactionary. He wanted a return to the autonomous modernist abstraction whose efficacy could be judged by its one-dimensionality– that is, by its elementary pictorial and anti-situational nature. Fried looked back nostalgically at a lost past where images and the reality they represented were distinct from each other. In confusing the teleologies of “presentness” and “theatricality” and neglecting their political implications, he mistook a setting sun for the dawn.

The paranoid diatribe that is Art and Objecthood set up an asymmetrical dichotomy between “presentness”– the immediacy of an image’s consumption by the viewer, and “theatricality”– objects which need the viewer herself to mediate the act of consumption. Insofar as this crooked duality serves to differentiate between two image forms– that of the spectacular image which can be completely consumed immediately, which is distinct from the theatrical object which can only ever be incompletely consumed through a more dissociative mediation– Fried’s logic is sound. It is upon the arrival of his critical judgment that the contemporary reader becomes concerned for his psychological well-being. His qualification that so-called “theatrical” forms (images, objects, or otherwise) which cannot be apprehended as wholly “present” are not merely lesser, but are “at war with art as such” set a standard for visual art which foreclosed on the development of any critique outside that of readability and immediacy.14

The insufficiency of his unilateral determination of theatricality resulted in an art historical confusion obfuscating a novel emerging subjectivity and the classical dichotomous dynamic of the gaze. The conception of the gaze as it concerns our subject at hand it is best characterized by Jacques Lacan while waxing poetic about the time he roleplayed as a fisherman: “In the scopic field, everything is articulated between two terms that act in an antinomic way– on the side of things, there is the gaze, that is to say, things look at me, and yet I see them. This is how one should understand those words, so strongly stressed, in the Gospel: ‘They have eyes that they might not see.’ That they might not see what? Precisely, that things are looking at them.”15

In misquoting biblical moralism Lacan solidifies the turning back of the gaze as a position which is compensatory, and thus passive. The gaze’s reversal captures completely the viewing-subject-cum-viewed-object. The dissociative operation by contrast activates the viewing-subject into a projecting-subject where the subject sees her seeing eyes. This is how we should read Fried’s misinterpreted gaze-anxiety. The dissociative operation is a shift in understanding the theatricality of the gaze to one where the subject’s point-of-view no longer originates in the physical eye of the beholder, but from a dislocated perspective which sees the subject’s own viewing eye as it simultaneously performs the principal act of viewing. The effects of this shift expand the field of spectatorship rather than invert its relations or offer some “third position.”16

Fried located anxiety, tension, and disquiet in minimalist sculpture. Which is to say that in psychoanalytic terms Fried thought he found the Other inside human-sized geometric shapes. While the unease Fried felt when viewing a Tony Smith sculpture is a feeling he doubtlessly experienced as sheer terror– it was not the well established sensation the subject experiences in realizing that the object gazes back. Instead it was an instance of dissociation. Fried was not extorted into a situation with a Tony Smith sculpture which returned his gaze– in truth his experience was a dissociative vision of seeing himself seeing the Tony Smith sculpture. In this way he was no longer a unified or pure viewer, as now he performed his role as viewer. When we contextualize Fried’s vehement antitheatricalism in the text’s absence of politics we find this most basic phenomenology of “presentness” to be little more than a thoughtless affirmation of the same tautology of Guy Debord’s Society of the Spectacle, published in the very same year. Debord laid out spectacle’s totalitarian “social relations between people that are mediated by images” which are consumed as immediately as they are produced.17 In effect Michael Fried glorifies this aesthetic function. While Fried’s point of departure for “presentness” is ostensibly relevant only to the field of visual arts, Debord’s theory of spectacle insists upon its molecular totality that imposes itself everywhere. In this way Fried’s “critique of culture,” could and should have been contextualized as part of a broader “unified critique dominating the whole of culture that no longer separates itself from the social totality.”18 Given that the direct financial support of certain artists, styles, and genres of modern art by the CIA, laundered through various fronts and foundations such as the Congress for Cultural Freedom, the Hoblitzelle Foundation, Association Française d’Action Artistique, among others, is by now well established,19 it is curious that the artistic theory which validated precisely the “presentness” espoused by Fried, Greenberg, and other chauvinists of the era has hitherto gone unchallenged.

It was the fact that an artwork might exist in the world just the same as the person witnessing them that both heralded the seedlings of postmodernism. Distinct from the paranoid exhibitionism of the classical gaze, dissociative theatricality implicates the viewer doubly. The viewer views the work as they view themselves viewing the work. In the philistine’s own words: “the presence of theatricality is a function of the special complicity that that work extorts from the beholder.”20 This structure is teleological insofar as the interpretation of what constitutes “theatricality” shifts with the times. Fried’s accounting continues to dominate the field of what is possible in visual art and in many ways this aesthetic domination is stronger now than it ever has been, especially when one considers the advent of instagram and online viewing platforms as new sites for the immediate consumption of images. The interesting differentiation between Fried against Debord’s conceptions of presentness or spectacle is that where Debord found no possibility of evading the spectacle save its “total negation,” Fried intuited that theatricality could in fact offer some prospect, however slight, to regard images (paintings, sculptures, life, etc) as objects and thus inhibit their complete consumption. And it was this blockage that ensured his essential contempt for the concept.21

As proposed by Elan Keir, the hallmark of theatricality is its production of quotation marks around its bodies, actions, and objects. It is these quotation marks which offer the newly created “subject-actor”, not so much any new ability to subvert spectacle à la the situationist détournement, as an oblique dynamic of radical dissociation. If one had not yet noticed, now is the time to be radically dissociating. When judged with the view of the contemporary youth’s growing penchant for horse tranquilizer– evidenced by a 1200% increase in estimated recreational ketamine use between the years 2002–2022; dissociation, whether as a form of recreation or as a mode of being and perceiving in the world, seems to be undeniably of our time.22

iii.

It is often said that the road to hell is paved with good intentions; unfortunately for the mass of those humans who call themselves “thinking,” it is rarely the pavers who understand the implication. In order to trace the path of theatricality in visual art from Fried’s reactionary notion of it– that is, his prohibition on mediated consumption– toward a more dissociative perspective of art, we need to take account of those artistic trends that took theatricality to be such a literal concept that their existence could only be affirmed through their literal use, activation, or experience by a viewer. In other words, we must recount the great fraud of Relational Aesthetics.

Regardless of the conservative inanity of Fried’s antiquated sentiments, a visual art that had largely spurned “theatricality” as a discursive framework was famously good for business, and so there should be few questions on why it went mostly unchallenged for 30 years. There were of course challengers and dissent to the regime of presentness, all of which were briefly tolerated before they could be refined into fodder for the canon and its market. It was only in the 1990s that a maniacally optimistic snake-oil salesman by the name of Nicolas Bourriaud announced loudly and proudly that “theatricality” was back. They had done it, after years of relentless shelling, curators such as Maria Lind, Hans Ulrich Obrist, Barbara van der Linden, Hou Hanru, with Bourriaud leading the unit, had breached what they thought was a wall between “art” and “life.” In reality the only boundary that was breached was more of a rickety chain-link fence barely separating the sacred autonomous status of art from the field of full blown spectacle.

On paper, so-called relational aesthetics claimed to be “an art form where the substrate is formed by inter-subjectivity, and which takes being-together as a central theme, the ‘encounter’ between beholder and picture”23 In less bourgeois terms: relational art claimed to s(t)imulate social experiences in “civic space,”24 using the artwork itself to mediate interpersonal relations. If, on paper, it sounds a lot like the fourth thesis on the first page of The Society of the Spectacle, quoted earlier, that is because it is nearly identical to Debord’s definition of spectacle as “the social relation between people that is mediated by images.”25 As might be expected, what was advertised on paper corresponded very little to the effects in real life. It is through the lens of effects and results over intentions and rhetoric that one should judge relational aesthetics.

The most immediate problem of relational art is the absolute impossibility of interpretation. In her thoughtful critique of Bourriaud’s relational aesthetics, Claire Bishop describes a shift where “rather than the interpretations of a work of art being open to continual reassessment, the work of art itself is argued to be in perpetual flux. There are many problems with this idea, not least of which is the difficulty of discerning a work whose identity is willfully unstable.”26 This “willful instability” is a position which serves as a plausible deniability obfuscating aesthetic judgment. Relational aesthetics spawned an entirely new rhetorical determination of semiotization. In shifting the prescription of an object’s aesthetic taxonomy from the physical space in which it existed– the exhibition space or the theatre for example– to dictation by various experts, relational aesthetics succeeded in decoupling the process of semiotization from physicality. No longer was something determined to be art because of its physical context or intrinsic qualities, whether it was “contextualized” in a museum or a gallery or on a stage; or a painting on the wall of a private residence. This shift may appear to be a discrepancy in details, but the effects of such a dissociating maneuver had effects only similar in scale to the potentially analogous dollar-gold decoupling of the Bretton Woods annulment. The effect of relational art was that any object, image, or situation’s status-as-art was now dictated to the viewer by institutions, curators, and/or “artists.”

This taxonomy can be summarized as such: Relational art is fundamentally didactic– it is what they say it is. Theatricality on the other hand might be thought of as auto-didactic– it is what it says it is. Of course the axiomatic is not new, nor was it new in the 1990s. What was exceptional however was how this axiomatic was instrumentalized by some relational art in order to offer spectacularized and simulated versions of basic services, such as soup kitchens or public libraries. Perhaps it is due to its supposition as low-hanging fruit that Bishop did not comment on this glaring embarrassment, nevertheless one should make note of the decadent optics of much of the genre. For example, that a wealthy gallery-going public gathering in an affluent part of a city to eat free soup as a means of “mediating social relations” in the same city where there are people who cannot afford soup as a means of mediating hunger, is a gesture of the most base fetishism.

A most interesting quality about Bourriaud’s ideology is his almost Stalinist view on the efficacy of art. As he makes clear, art has a purpose, and its purpose is basic services and remedial labor, “through little services rendered, artists fill in the cracks in the social bond.”27 His lip service to mutual aid efforts or Lenin’s concept of dual-power has no such revolutionary ends in mind, as these “social cracks” were only ever intended to be filled by art temporarily, for the duration of an exhibition. Following the closing of the show, the hungry or library-deprived are destined to return to their respective cracks. We can see Bourriaud’s naive demand for total undivided subjects building temporal “microtopic communities” less as a reasoned resistance to the inherent anti-sociality of the New Global Economy, and more of a desperate plea for undivided attention, social cohesion, and delusional desires of conviviality in an increasingly fragmented society.28 Even if we are to consider all this in good faith, we still must ask from where the impulse to reject antagonism comes. The denial of antagonism’s imperative societal and political presence is not only aggressively retrograde, it is also a militant affirmation of a deleterious hegemonic ideology which would in a matter of 30 years prove apocalyptic.

One would hope that Bourriaud’s attempt to classify some individual’s hospitality, mutual aid, sociality, and conviviality as art forms would be rooted in Benjamin’s historicization of art forms as predictive, or at least manifesting the desire for some yet-to-be-realized future, but in reading Bourriaud’s actual texts, one cannot be certain.29 This operation is a totalized reification of Hal Foster’s theory of aesthetic pluralism. Where “no style or even mode of art is dominant and no critical position is orthodox. Yet this state is also a position, and this position is also an alibi.”30 Language and cultural capital replaced the architecture of semiotization– the stage and the exhibition as sites that had the ability to grant semiotizing “quotations” around bodies and objects. An aesthetics that necessitates an artwork’s actual functional “use” is an extremely simplistic misunderstanding of “theatricality.” When Veltruský said that “All that is on the stage is a sign,” he did not mean that the janitor washing the stage’s floor after a performance becomes a performer, or his mop a prop, by their mere presence “on the stage.”31 Using an artwork instead of contemplating it does not magically sublimate aesthetics into social relations. Instead it just negates any possibility of developing a cohesive theory of aesthetic judgment divorced from identity. Bishop concludes her critique by taking particular issue with the affirmative nature of Bourriaud’s “microtopic” relational art, which ignores any ideas of “relational antagonism that would be predicated not on social harmony, but on exposing that which is repressed in sustaining the semblance of this harmony.”32

If “presentness is grace,” then theatricality is antagonism, and antagonism is something sorely lacking from all aspects of contemporary culture.33

To which could only be added: For an aesthetics which proclaimed itself to be above all else, political, ethical and convivial, relational art has served as little more than an unsavory celebration of the West’s transition to a service economy. A transition, it should be noted, that has proved disastrous not only for the planet’s ecological stability, but as well as for the hundreds of millions of exploited sweatshop workers in Asia and the sub-continent now destined to produce the West’s endless thirst for cheap disposable commodities– not to mention the immensity of social atomization and scapegoating subsequently generated in those economies when the very same workers whose jobs were outsourced to far away places found their factories shuttered and a job market they were unprepared for. We don’t need to try to construct yet another critique of spectacle’s Empire, attempting to subvert it or evade it, but at the very least we should never again allow ourselves to be duped into celebrating, let alone, affirming, its indelible dominance.

iv.

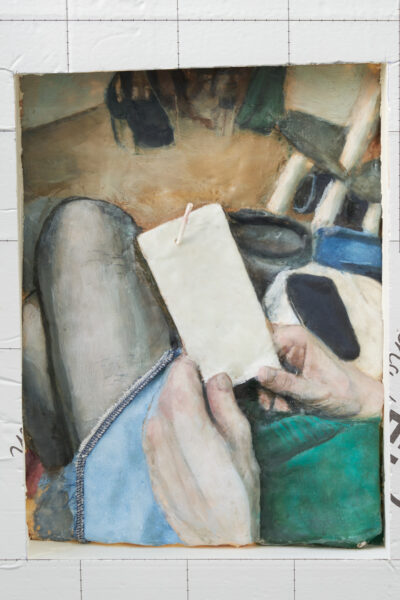

Alas, there is an elephant in the room– rather there are elephants in the room. If they are not elephants then they are most probably Mathilde Fenger’s paintings which depict scenes of Danish troops in Afghanistan during the NATO / American occupation there. They are the only paintings which hang on the walls of this exhibition. Owned by the Danish military, normally these paintings are installed in a military training academy in Frederiksberg, as well as a base in Holstebro. Fenger’s battle paintings rest uneasily in this church34 of contemporary art that we have built for ourselves. But just as uneasily as they hang on these white walls, do we view them. If sculptures are those things that we bump into when trying to get a better physical view of a painting, what are those things that we bump into when we back up in horror as we behold ourselves beholding mass murder that we pay for? And it is from this position that we enter into the gauntlet of art’s essential efficacy.

In the act of dissociation, as a viewer goes through a process of derealization– when they see themselves among others looking at art and being gazed back by the painted images– when they see themselves from outside themselves, there is a rupture between the subject and her identity. The dissociation of identity offers a constructivist perspective where subjects might see how, for example, their role as a member of the professional-managerial class as an employee for a multinational pharmaceutical corporation is as performative and constructed as the dynamics at play in her temporary viewer-status. As a preliminary model, dissociation provides a framework for individuals to instrumentalize specific partitions of their divided subjectivity without risking identity. In elaborating this, we can see how identity, having grown so deeply and darkly neurotic– is something that has been constructed for us no matter how differently we may feel about the matter. In the dissociative operation, a subject can freely perform or not perform the identities that traditions and cultures have constructed for them. The mechanics of dissociation further allow the proper conditions to evade, however slightly, the subject’s total inversion into object. Dissociated subjects, having been implicated by their dissociated objects, are in a state of divisional flux, free to associate or dissociate more or less as they please. As such, the dissociated subject has no inversion, no reversal. As a mathematical equation, dissociation has negation as its only possible negative form, and as we know, “negation may reverse into pleasure, not into affirmation.”35

Ryan Cullen

1 Rancière, Jacques. Dissensus: On Politics and Aesthetics. Continuum, 2010, p. 139.

2 “Sculpture is something you bump into when you back up to look at a painting.”

3 Veltruský, Jiři “Man and Object in the Theater.” In A Prague School Reader on Esthetics, Literary Structure, and Style, 83–91. Washington D.C.: Georgetown University Press, 1964.

4 Elam, Keir. The Semiotics of Theatre and Drama. Methuen, 1980, p. 6.

5 Winnicott, D. W. “Transitional Objects and Transitional Phenomena.” Playing and Reality, Tavistock Publications, 1971.

6 Patrick Allen.

7 Eco, Umberto. A Theory of Semiotics. Indiana University Press, 1976, p. 225.

8 Fried, Michael. “Art and Objecthood.” Art and Objecthood: Essays and Reviews, University of Chicago Press, 1998, pp. 148-172. Originally published in 1967.

9 Ibid pp. 42.

10 Ibid p. 154.

11 Ibid p. 155.

12 For what else could cause such paranoid delusions as “the minimalist sculpture won’t stop looking at me”?

13 Fried, Michael. “Art and Objecthood.” Art and Objecthood: Essays and Reviews, University of Chicago Press, 1998, p. 148. Originally published in 1967.

14 Fried, Michael. “Art and Objecthood.” Art and Objecthood: Essays and Reviews, University of Chicago Press, 1998, p. 163. Originally published in 1967.

15 Lacan, Jacques. The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis. Translated by Alan Sheridan, W.W. Norton & Company, 1998, p. 109. Originally published in 1978.

16 Rancière, Jacques. The Emancipated Spectator. Translated by Gregory Elliott, Verso, 2009, p. 63.

17 Debord, Guy. The Society of the Spectacle. Translated by Donald Nicholson-Smith, Zone Books, 1995, p. 4. Originally published in 1967.

18 Ibid. p 111.

19 For a comprehensive accounting of the CIA’s activities in the visual arts during the cold war see: Saunders, Frances Stonor. Who Paid the Piper. Granta Publications, London, 1999.

20 Fried, Michael. “Art and Objecthood.” Art and Objecthood: Essays and Reviews, University of Chicago Press, 1998, p. 155. Originally published in 1967.

21 Debord, Guy. The Society of the Spectacle. Translated by Donald Nicholson-Smith, Zone Books, 1995, p. 106. Originally published in 1967.

22 Results collated from annual reports by: National Surveys on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH): Summary of national findings. SAMHS. Rockville, Maryland. 2003–2023. The European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA). Lisbon. 2003–2023.

23 Bourriaud, Nicolas. Relational Aesthetics, Presses du réel, Paris, 2002. p. 7.

24 “Civic space” here of course referring to a museum, or biennial to which one must pay an entrance fee

25 Debord, Guy. The Society of the Spectacle. Translated by Donald Nicholson-Smith, Zone Books, 1995, p. 1. Originally published in 1967.

26 Bishop, Claire. “Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics.” October, no. 110, 2004, p. 65.

27 Bourriaud, Nicolas. Relational Aesthetics, Presses du réel, Paris, 2002. p. 44.

28 Ibid. p. 13.

29 Benjamin, Walter. “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” Illuminations, edited by Hannah Arendt, translated by Harry Zohn, Schocken Books, 1968, p. 217-251. Originally published in 1936.

30 Foster, Hal. “Against Pluralism.” Recodings: Art, Spectacle, Cultural Politics, Bay Press, 1985, p. 13.

31 Veltruský, Jiři “Man and Object in the Theater.” In A Prague School Reader on Esthetics, Literary Structure, and Style, 83–91. Washington D.C.: Georgetown University Press, 1964.

32 Bishop, Claire. “Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics.” October, no. 110, 2004, p. 79.

33 Fried, Michael. “Art and Objecthood.” Art and Objecthood: Essays and Reviews, University of Chicago Press, 1998, p. 172.

34 Cult more accurately, see: Bender, Annika. Death of an Art Critic. Sternberg Press, 2006.

35 Adorno, Theodor W. Aesthetic Theory. Translated by Robert Hullot-Kentor, University of Minnesota Press, 1997. Originally published in 1970, p. 108.

![]()

![]()